Reamer Information

What is a Reamer?

Reamers are rotary cutting tools with one or more cutting elements used to enlarge to size and contour a previously formed hole.

Its principal support during the cutting action is obtained from the workpiece.

Types of Reamers

Chucking Reamers

Chucking reamers are the most widely used type, typically employed in lathes to enlarge and smooth out pre-drilled holes. They are versatile and suitable for various applications where precision finishing is required. These reamers are usually made from high-speed steel or tungsten carbide, offering a balance between cost and durability.

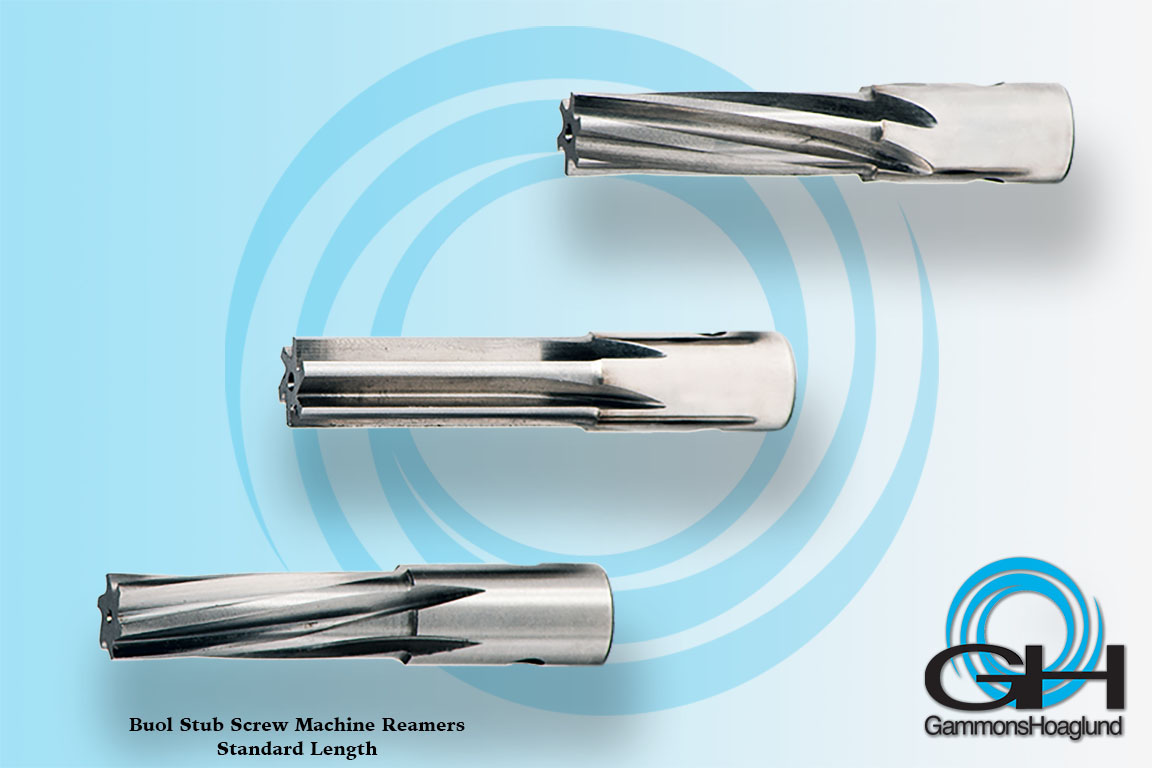

Stub Reamers

Stub reamers are shorter reamers used in tight spaces or where only a small amount of material needs to be removed. They provide precision finishing in confined areas and are ideal for applications requiring a rigid tool with minimal overhang.

Stub reamers are shorter reamers used in tight spaces or where only a small amount of material needs to be removed. They provide precision finishing in confined areas and are ideal for applications requiring a rigid tool with minimal overhang.

Morse Taper Reamers

Morse taper reamers are specifically designed to finish Morse taper holes or sleeves, ensuring a precise fit for tapered tools and spindles. They are essential in applications requiring accurate taper dimensions and are commonly used in machining and tool maintenance.

Morse taper reamers are specifically designed to finish Morse taper holes or sleeves, ensuring a precise fit for tapered tools and spindles. They are essential in applications requiring accurate taper dimensions and are commonly used in machining and tool maintenance.

Automotive Reamer

Automotive reamers are used to ream steel components in vehicles, such as steering arms, ball joints, and tie rod ends. These reamers are built to handle the tough, often high-strength steel materials found in automotive parts, providing reliable performance and longevity.

Automotive reamers are used to ream steel components in vehicles, such as steering arms, ball joints, and tie rod ends. These reamers are built to handle the tough, often high-strength steel materials found in automotive parts, providing reliable performance and longevity.

Die Maker Reamers

Die maker reamers are specialized tools used to create precision tools like die sets, punches, and steel rule dies. They are designed for high accuracy and durability, ensuring that the tools produced meet exacting specifications for industrial applications.

Welding Equipment Reamers

Welding equipment reamers are used for precision finishing in welding guns, cap-type electrodes, and other welding equipment. These reamers help maintain the integrity and performance of welding tools, ensuring consistent and high-quality welds.

Taper Pin Reamers

Taper pin reamers are designed to create tapered holes for taper pins, which are used to secure parts in mechanical assemblies. These reamers ensure a precise taper fit, critical for the reliable performance of machinery and equipment.

Jarno Reamers

Jarno reamers are used to finish Jarno taper holes, ensuring precise taper dimensions for machine tool spindles and precision applications. They are essential for maintaining exact taper specifications in high-precision environments.

Brown and Sharpe Reamers

Brown and Sharpe reamers finish Brown and Sharpe taper holes, ensuring accurate taper dimensions for older and some modern machine tools. They are crucial for maintaining the accuracy and performance of equipment using this taper system.